When I think about racism, segregation and the systems put in place to reinforce them, the Dan Ryan Expressway comes to mind. In part because of the complexity of it.

The Dan Ryan runs eleven miles, from 95th Street on the Far South Side to what’s now known as the Jane Byrne Interchange – the point where the Dan Ryan, the Eisenhower and the Kennedy meet.

As you drive north on the Dan Ryan, you see the skyscrapers of downtown rising up like Oz at the end of the yellow brick road. Fourteen lanes of traffic serve 300,000 people a day by one count. It’s either packed with cars during rush hour or, in off-peak times, Mario Kart come to life.

The Dan Ryan is not for the faint of heart or student drivers.

Growing up, the Dan Ryan was Chicago for me. A fearsome, muscular roadway that also sported a 75-foot-long, 40-foot high set of flashing red lips. Schools, businesses, and culture lined it. The Dan Ryan’s road signs tantalized with exciting places to visit if you took this exit or that one. Two versions of Comiskey Park, home of the Chicago White Sox, have towered over it at 35th Street.

American Pharoah notes the Dan Ryan Expressway was one of three expressway systems built under Mayor Richard J. Daley – the Stevenson and the Kennedy are the other two. Its construction was made possible through the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956.

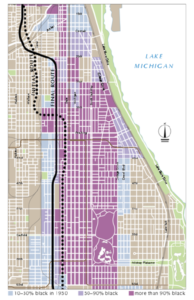

The book also argues that it reinforced what had up until then had been a historical dividing line between Black and white Chicago neighborhoods.

The original plans for the Dan Ryan called for it to cross the Chicago River almost directly north of Lowe Avenue, Daley’s own street, and then to jag several blocks, at which point it would turn again and proceed south. But when the final plans were announced the Dan Ryan had been “realigned” several blocks eastward so it would instead head south along Wentworth Avenue. It was a less direct route, and it required the road to make two sharp curves in a short space, but the new route turned the Dan Ryan into a classic barrier between the black and white south sides.

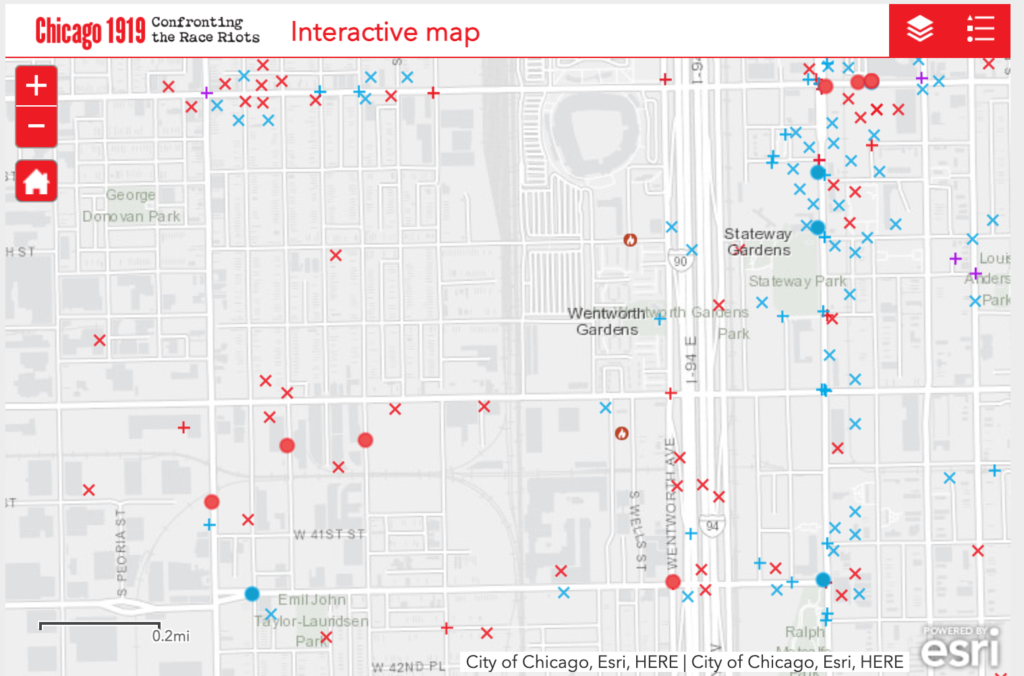

Langston Hughes was beaten up for crossing Wentworth Avenue, an unofficial dividing line between Chicago’s Black Belt and the white neighborhoods of the South Side. This included Bridgeport where Daley grew up. It was a line defended with violence by the Hamburg Athletic Club, of which Daley was a member in his youth, during the period of the 1919 race riots. “Athletic clubs” or “youth clubs” in this time were often covers for white gang activity or political power – or both.

The Dan Ryan’s 14 lanes of traffic would make it much harder to cross Wentworth Avenue by creating a significant obstacle in access to it from the east.

Pharoah also notes the construction of the Dan Ryan was announced less than a month after the City Council approved the building of the Robert Taylor Homes. The Robert Taylor project would be built in the State Street Corridor where other large public housing was already located: the Harold Ickes Homes, Dearborn Homes, and Stateway Gardens.

The overwhelming majority of the people in these communities were Black and lacked access to higher-income jobs, in large part because of the warehousing approach Chicago and other large cities used to provide housing that clustered Black people in parts of the city that separated them from white people.

The State Street housing projects, almost all of which are now long gone, were located just east of the Dan Ryan, which was just east of Wentworth Avenue. The violence that occurred in the 1919 riots, often from whites going into Black neighborhoods, was concentrated in a few places, particularly along State Street, decades before the Dan Ryan was contemplated.

The construction of the Dan Ryan in close proximity to the housing projects of the South Side did not increase the access of their residents to the opportunities of jobs, commerce, and attractions. If anything, it reinforced the lack of access. A 1998 New York Times article quotes one resident of the Robert Taylor Homes describing the projects as a “public aid penitentiary.”

It’s hard to find a more obvious metaphor for Chicago segregation. But the way the story plays out is more complicated than it would seem.

The racial makeup of many South Side neighborhoods changed significantly in the years following the construction of the Dan Ryan with many previously white neighborhoods becoming majority Black. According to a June 2020 report from the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning, Bridgeport itself is now 39% Asian, 33% white, 23% Latino, and 2% Black.

As a WBEZ Curious City segment points out, the Dan Ryan didn’t create the segregation in this part of the city. The story notes author Dominic Pacyga’s Chicago: A Biography says that “political power, street gangs, railroad viaducts, and railyards — posed greater obstacles to blacks’ expansion into white neighborhoods.”

Another source in this piece says the Dan Ryan “helped expedite the exodus of the white community from the Southwest Side.”

It’s an inescapable fact that Chicago’s built environment often reinforced or exacerbated segregation. And that’s before you get into the history of redlining and other ways in which racism and real estate intersected.

It’s an inescapable fact that Chicago’s built environment often reinforced or exacerbated segregation. And that’s before you get into the history of redlining and other ways in which racism and real estate intersected.

For instance, in the map for the WBEZ segment, the proposed and final routes of the Dan Ryan are shown. The final route meant more Black-owned homes that white homes would be eliminated to make way for the expressway.

When you consider how Black families have more of their assets and wealth concentrated in their homes than white families you see the institutional effects of racism are often complex and indirect.

—

Now, none of us built the Dan Ryan Expressway; it opened in 1961 – years before many of us were born. We weren’t consulted about the route. But the 300,00 people who use it each day benefit from its convenience and speed. We can’t ignore that.

Should we tear up the Dan Ryan Expressway and rebuild it completely? No. Nobody’s arguing that.

We should still recognize that the construction of it reinforced a desire on the part of those who built it to keep Black people and white people separated.

Besides, it’s not like the use of the Dan Ryan Expressway is killing black motorists at a higher rate than white motorists.

Or the tools and training given to the staff of the Illinois Department of Transportation put them in a position where they have to choose between their lives or the people using the road.

Or we have to hold fundraisers because we aren’t equipping them with enough fluorescent vests to wear when they are in harm’s way.

Or the people who work at IDOT are committing suicide at a higher rate than the national average.

If that were happening, we’d definitely need to think about a complete rebuild because it’s harming everyone involved.